Food Justice is About Us, Not You

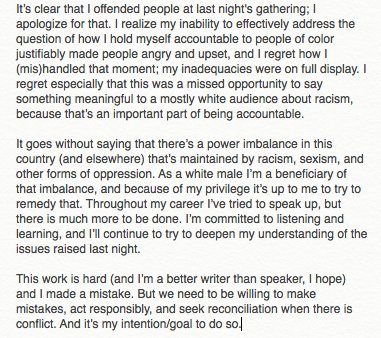

As white-led food and farming organizations begin to grapple with the topic of race, I repeatedly hear my white colleagues talk about race in terms of their feelings. They feel bad that it happens, they ask what they need to say differently, and, when confronted with an instance in which they or their organization perpetuates systemic racism, they focus on their personal shortcomings. White people see race as a personal problem, while people of color know it is a systemic problem. This critical difference in perspective hinders us from making necessary structural change.We saw an example of this last week at events that transpired at the Young Farmers Conference in New York, hosted by Stone Barns. Mark Bittman and Ricardo Salvador gave a keynote on the first day. During the question and answer period, Nadine Nelson and Dallas Washington asked Mark Bittman questions about race in relation to his and the food movement’s work. The New Food Economy reported on this and several videos of the exchange are available online, so is common knowledge who said what. But the individuals involved shouldn’t be the focus. We can use this situation to blame particular people, but it will have little effect. What we might see in this, instead, is systemic racism, how it acts through us, and the responsibilities individuals have to respond to it.What I will focus on is not what happened in the question and answer period, but Bittman’s response. It is as follows: This statement misses the point of what was offensive and what needs to be remedied. What was offensive was his avoidance of addressing systemic racism imbued in food writing and in the land access framework he espouses. Bittman seems to think the problem is about him, that remedy is through his personal transformation. He writes how it was a missed opportunity for him to talk about race and to be accountable. That he swears he is committed to listening and learning, that he just made a mistake. What he is making here, in case you missed it, is a request for his personal redemption. This is a move familiar to people of color: the offending white person appeals to their humanity and asks us to work with them so they can be a better person.That is white privilege. Systemic racism enables white people to assert their personhood and be seen for the complexity of who they are for their potential to change. When a person of color makes a mistake, they are seen by society as symbolic of their entire race, ethnicity, or of all people of color and of broad, negative stereotypes. (Sometimes we have to joke about it.) We, people of color, are not seen for our personhood.We, people of color, are not seen for our complex personhoods. But we should be. Our personhoods embody a multitude of identities and histories – races, culture, gender, age, migration, displacement. We live them every moment, and our multiple, intersecting identities come into play in our engagement with people and politics. For farmers of color, these intersections are particularly rich. A conversation about race is not and cannot be separated from a conversation about farming, food systems, and sustainability—and vice versa.When Bittman—or any white person in a position of power, from conference organizers to social media mavens—chooses not to talk about race, or passes the mic so others can talk about it, we see another example of how white people think about race: as a separate topic. White people seem to need too often to designate a separate time and place to talk about race. At another young farmer conference I attended in 2016, they offered concurrent tracks about the Farm Bill and about race. True, the Farm Bill provides substantial funding for nutrition programs, farm technical assistance, and other food and farming programs. But historically, it began as a tool to support white farmers, explicitly excluding black farmers. This history, its legacy, continues to have an effect. The Farm Bill and race are not separate topics.The same holds true for discussions of land access, marketing, seed sourcing, and every and all farm topics. We don’t need special sessions about race, we need race to be meaningfully included as a topic in all of our discussions. If you don’t know how race is relevant to say climate smart farming, don’t assume it doesn’t—ask someone who might know. Our conversations need to be integrated—and please consider the full weight of that word—if we are to create systemic change.Ironically, the framework for understanding these relationships were clearly presented at the beginning of the Conference by Shakirah Simley, Viviana Gilbuena, Hannah Koski, and Margiana Peterson-Rockney in their talk about Agroequity. Race is discussed at pre-determined, circumscribed times.Working with people of color to shape our farming conversations and policies requires respecting the knowledge of people of color. Don’t tell us you want to listen: tell us you’re going to collaborate to create a meaningful space in which to speak, not about race, but about the topics you don’t normally think are “ours” to talk about. This is true power sharing, After all, there’s no opportunity to listen if you don’t give us time at the podium.Undoing racism requires an understanding of how systemic racism permeates everything. Doing so enables people to comprehend how it is actualized through them, how they reproduce it, and thus how to prevent it. I hope you will join in the collective task of dismantling racism because it is about all of us.

This statement misses the point of what was offensive and what needs to be remedied. What was offensive was his avoidance of addressing systemic racism imbued in food writing and in the land access framework he espouses. Bittman seems to think the problem is about him, that remedy is through his personal transformation. He writes how it was a missed opportunity for him to talk about race and to be accountable. That he swears he is committed to listening and learning, that he just made a mistake. What he is making here, in case you missed it, is a request for his personal redemption. This is a move familiar to people of color: the offending white person appeals to their humanity and asks us to work with them so they can be a better person.That is white privilege. Systemic racism enables white people to assert their personhood and be seen for the complexity of who they are for their potential to change. When a person of color makes a mistake, they are seen by society as symbolic of their entire race, ethnicity, or of all people of color and of broad, negative stereotypes. (Sometimes we have to joke about it.) We, people of color, are not seen for our personhood.We, people of color, are not seen for our complex personhoods. But we should be. Our personhoods embody a multitude of identities and histories – races, culture, gender, age, migration, displacement. We live them every moment, and our multiple, intersecting identities come into play in our engagement with people and politics. For farmers of color, these intersections are particularly rich. A conversation about race is not and cannot be separated from a conversation about farming, food systems, and sustainability—and vice versa.When Bittman—or any white person in a position of power, from conference organizers to social media mavens—chooses not to talk about race, or passes the mic so others can talk about it, we see another example of how white people think about race: as a separate topic. White people seem to need too often to designate a separate time and place to talk about race. At another young farmer conference I attended in 2016, they offered concurrent tracks about the Farm Bill and about race. True, the Farm Bill provides substantial funding for nutrition programs, farm technical assistance, and other food and farming programs. But historically, it began as a tool to support white farmers, explicitly excluding black farmers. This history, its legacy, continues to have an effect. The Farm Bill and race are not separate topics.The same holds true for discussions of land access, marketing, seed sourcing, and every and all farm topics. We don’t need special sessions about race, we need race to be meaningfully included as a topic in all of our discussions. If you don’t know how race is relevant to say climate smart farming, don’t assume it doesn’t—ask someone who might know. Our conversations need to be integrated—and please consider the full weight of that word—if we are to create systemic change.Ironically, the framework for understanding these relationships were clearly presented at the beginning of the Conference by Shakirah Simley, Viviana Gilbuena, Hannah Koski, and Margiana Peterson-Rockney in their talk about Agroequity. Race is discussed at pre-determined, circumscribed times.Working with people of color to shape our farming conversations and policies requires respecting the knowledge of people of color. Don’t tell us you want to listen: tell us you’re going to collaborate to create a meaningful space in which to speak, not about race, but about the topics you don’t normally think are “ours” to talk about. This is true power sharing, After all, there’s no opportunity to listen if you don’t give us time at the podium.Undoing racism requires an understanding of how systemic racism permeates everything. Doing so enables people to comprehend how it is actualized through them, how they reproduce it, and thus how to prevent it. I hope you will join in the collective task of dismantling racism because it is about all of us.