The one thing my farm training never covered: Racism

When I started farming grains and vegetables in California in 2014, I already had a lot of the knowledge, skills, and experience essential to farming. When I was a child, my grandmother taught me to how grow plants and save seed. In college, I studied geography, focusing on atmospheric physics and later on soil science, which enabled me to assess landscapes and their hydrology and microclimates. After college, I created a restaurant that sourced from local farms, which gave me business skills I could apply to my farm.But this wasn’t nearly enough. I attended every farm conference, intensive, forum, panel, workshop, and field day I could. I sought apprenticeships and internships. I learned from other farmers how to scale up and efficiently cultivate and harvest. Through study and practice, I learned how to take on the immensely complex task of farming.But no farm conference, internship, or book prepared me for the challenges of farming as a person of color.I don’t want to be labeled the farm blogger who only talks about race, but it’s something I can’t ignore. Race permeates my life. It is something I live with and through, that we all live with and through, even as farmers. Racism isn’t unique to cities; in the country—in the bucolic landscapes in which we farm—it is also a problem, one that hinders a large segment of young farmers and keeps others from farming altogether.I’ve had farm advisors deter me from growing Southeast Asian crops, explaining, as if to protect me from something I didn’t understand, that there was no market for them. This despite the fact that there are over 4.9 million Asian Americans in California, the fastest growing demographic group in the state. At local markets, I’ve seen people shoo their friends away from my farm stand saying, “Asians don’t grow organic.” Others ask me if I speak English, using this as a precondition to purchasing. Even simply living in a farming area is hard. I’d avoid going to the only grocery store in 20 miles because I often see trucks flying Confederate flags parked out front. It isn’t uncommon for people to yell racial epithets at me or threaten violence as I walk down the street, telling me to “go home.”But this is my home. I farm in a rural area because that’s where farms can exist at a viable scale. But it keeps me far from family, friends, and an understanding community that affords me safety. At times, it has left me feeling confined to my farm. Needing camaraderie, I sought out farmers of color using Natasha Bowen’s The Color of Food website, which is an extension of her book that contains portraits and stories of farmers of color across America, plus a map of where they live and farm. I contacted the only farmer within 200 miles, Kristyn Leach of Namu Farm. We exchanged information about seed, cultivation, and marketing, but also shared solidarity, something more important than knowledge. My connection with Kristyn inspired me to convene other Asian American farmers to discuss market opportunities, collaborate on customer education, and share best practices. This group became the Asian American Farmers Alliance.

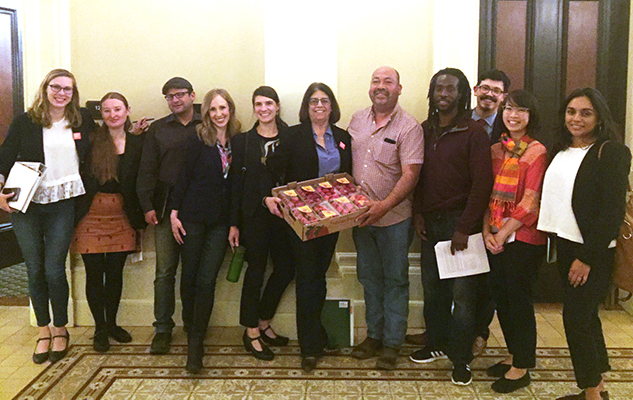

I’ve also learned a great deal from Dr. Carol Zippert of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, whom I’ve had the pleasure of befriending recently. She shares stories about how her community cooperated with one another to retain farmland, develop capital, and create jobs during segregation, Jim Crow, and state-sanctioned and socially-accepted oppression of African Americans. Her 50 years of rural community organizing showed me the power of cooperation to enable farmers of diverse backgrounds to thrive.This is the kind of knowledge that transforms and sustains farmers of color. It goes beyond technical knowledge, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be included in technical assistance trainings and conferences, like NYFC’s 2016 Leadership Convergence (pictured above). If more farmers of color were included in these presentations, this knowledge could be shared widely and made part of all our conversations. Marketing advice, for instance, could include how to address racist customers or how to be an ally to other farmers.This knowledge needs to be passed on and made actionable so that gains we make in our communities don’t need to be recreated by future generations. That’s where policy comes in.

Farm service organizations and farmers, including myself, have been working on legislation here in California to support farmers of color. The first we’re pushing for in our state legislation is AB 1348, the Farmer Equity Act. If passed, this bill would introduce a definition of socially disadvantaged farmers and thus acknowledge the historic and current experiences of farmers of color as distinct. It would include those who were enslaved, those who were robbed of land and citizenship, and those forcibly brought over for farm labor. With this recognition, it opens the door to technical assistance, resources, and programs for farmers of color. The bill is scheduled to go to the California Senate floor on July 6th, so I encourage Californians to call or write their assembly members to urge them to support the Farmer Equity Act.While young farmers develop as stewards, producers, and business owners, we as a society can advocate for equity so all young people have a chance to become successful farmers.